In the early 1980s, two students from the University of Bologna, Pierluigi Marconi and Roberto Ugolini, contacted Bimota to discuss future developments in motorcycle engineering. They were searching for a suitable topic for their thesis (Italian: Tesi). At the time, Bimota had earned an excellent reputation for its outstanding chassis designs. The company specialized in lightweight, rigid frames and swingarms. However, when it came to front forks, Bimota did not develop its own products but instead purchased high-quality telescopic forks from well-known manufacturers such as Ceriani or Marzocchi.

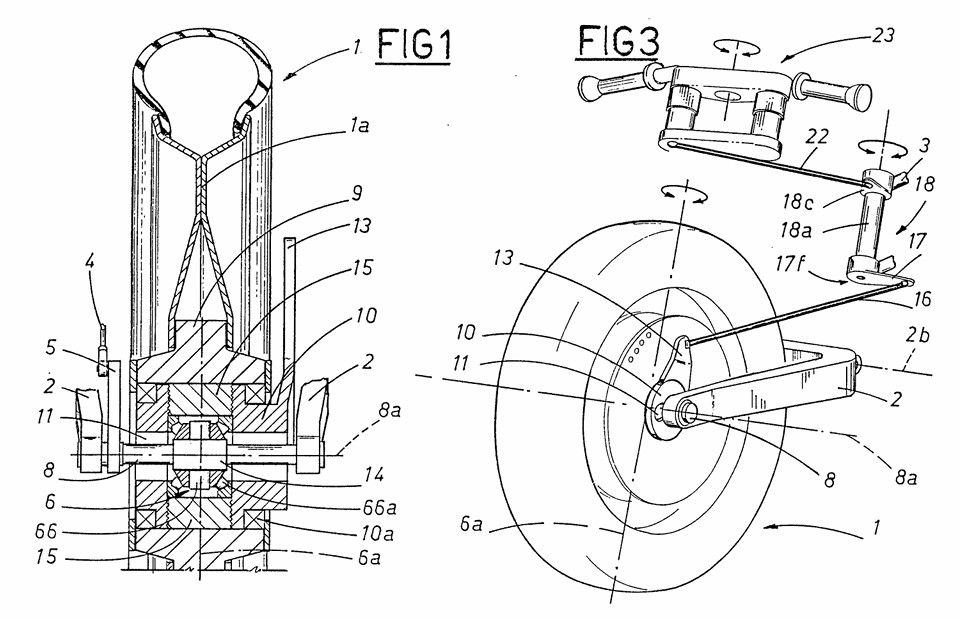

Published under Patent EP 0 432 107 B1

The front fork in a motorcycle chassis performs several functions:

- Guiding the front wheel

- Transmitting steering movement

- Absorbing and damping shocks

- Transferring forces to the frame

From Tamburini’s perspective, the telescopic forks of that era were the weak point of the chassis and reached their limits not only in racing. Especially under braking, the forces acting on the forks caused flex and deformation, leading to reduced suspension and damping response. Additionally, as the fork compressed, the chassis geometry changed, and the long leverage of the fork introduced high forces into the steering head. This was reason enough to search for alternatives. Thus, the topic for their thesis was found – designing an optimized front-wheel suspension.

Marconi and Ugolini developed a solution where the front wheel was guided by a double-sided swingarm and a hub-center steering system. However, the use of hub-center steering for motorcycles was not a new concept. It was first developed in the early 1920s by Carl A. Neracher, a German-American engineer. His company, the Neracar Corporation of Syracuse, produced the „Ner-a-Car,“ the first mass-produced motorcycle with hub-center steering. While Marconi and Ugolini’s design used the steering principle, it otherwise had little in common with Neracher’s solution.

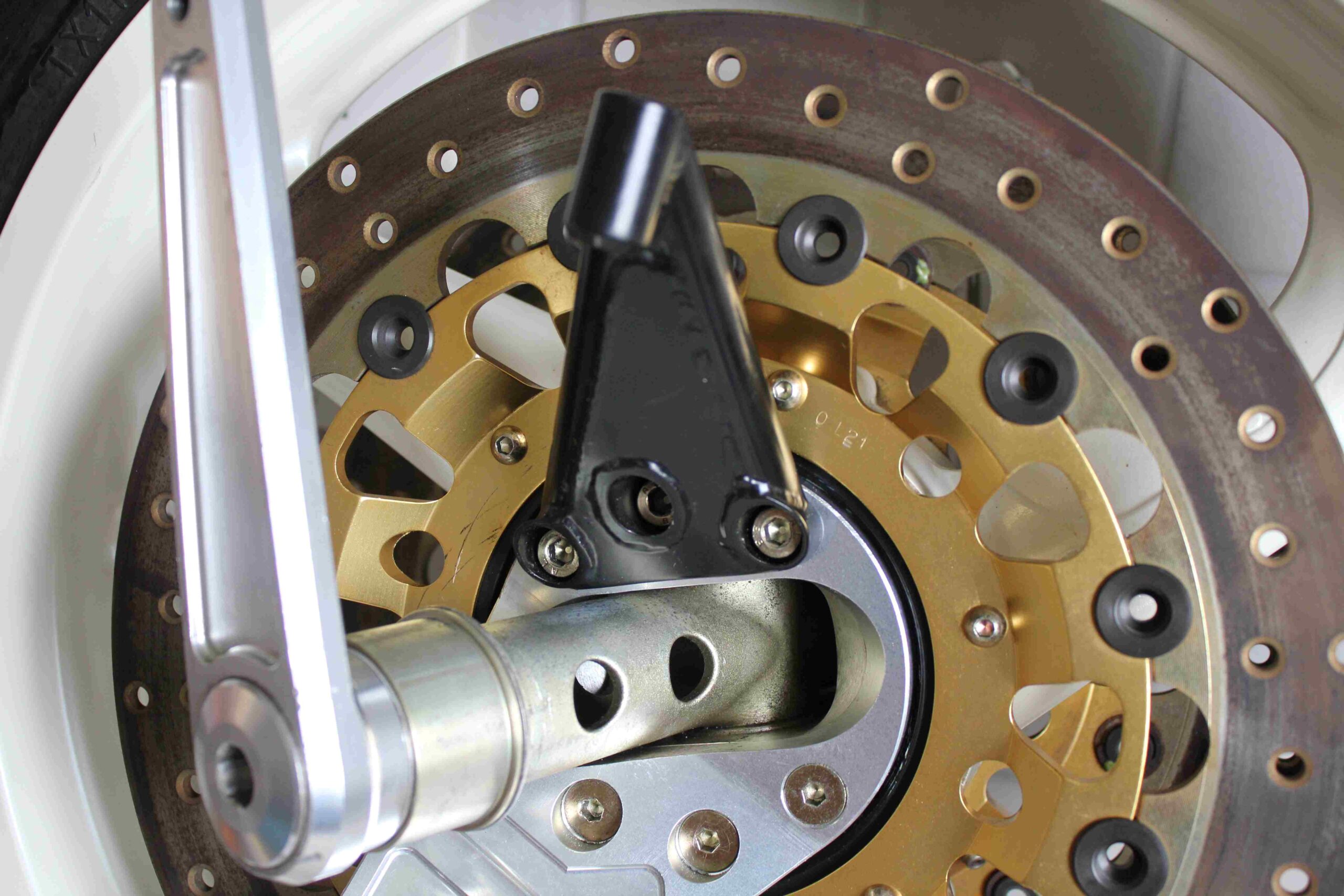

The key component of the hub-center steering system was the crosspiece within the wheel hub, which served as the wheel axle. The wheel rotated around one axis (the axle pin), while steering occurred around another (the steering pivot). The steering lever was connected to the fixed inner part of the wheel hub. The hub bearings had a significantly larger diameter than usual.

The hub-center steering system offered the design advantage of largely decoupling the aforementioned functions of front-wheel suspension. Additionally, the trail remained nearly constant during suspension travel. However, it also had inherent disadvantages. The steering angle was reduced due to the swingarm’s geometry, and the costs were significantly higher.

For Bimota, it made perfect sense to adopt a system where the benefits of separating suspension, wheel guidance, and braking force transmission outweighed the drawbacks of higher costs and limited steering angle. Both disadvantages were of minor importance in Bimota’s racing activities and their high-end customer models.

After completing their thesis, Bimota hired Pierluigi Marconi and Roberto Ugolini. Under the direction of Frederico Martini—since Tamburini had left the company that same year—they built a prototype, which was presented at the Milan Motorcycle Show at the end of 1983.

Photo provided by Dietmar Edel, Hadamar

The first prototype, unveiled at the 1983 Milan Motorcycle Show, was based on the engine of the Honda VF 400. The compact and narrow 90° V4 DOHC four-valve engine was ideal since the prototype had no conventional frame. Instead, the connection between the two swingarms was formed by a component bolted to the engine, made from a mix of aluminum, carbon fiber, and Kevlar, which also served as the lower fairing. The front swingarm’s shock absorber was mounted beneath the engine and connected via linkages.

Photo provided by Dietmar Edel, Hadamar

For transmitting steering movement, the developers preferred a hydraulic solution over a mechanical linkage. As seen in later production models, the mechanical solution was complex and prone to play. The hydraulic solution in the Tesi prototype was relatively simple: both the steering head and front wheel featured double-acting hydraulic cylinders. However, in later prototypes, this approach was abandoned due to poor feedback from the steering forces to the rider.

A year later, in 1984, the second prototype was developed with the Honda VF 750 engine for track testing. Bimota designed a two-part hybrid frame from carbon fiber and aluminum, bolted to the engine at the sides. The hub-center steering system was modified to allow for a second brake disc on the right side, where the steering lever was located. The steering movement was still hydraulically transmitted.

Photo provided by Dietmar Edel, Hadamar

In 1985, Bimota introduced the third prototype, again powered by the Honda VF 750 engine but with a completely new frame. The carbon-fiber composite frames of the earlier prototypes proved too expensive for mass production. Bimota opted for conventional materials, constructing the frame from a combination of milled aluminum plates and steel tubing. On each side of the engine, two aluminum plates were bolted—one for the front swingarm and one for the rear. These side plates were connected by two 35 mm steel tubes. The rear subframe and front frame were also made of steel tubing.

Photo provided by Dietmar Edel, Hadamar

Two more years passed before the next prototype, which marked a significant step toward series production. First, the hydraulic steering was replaced with a mechanical system. Second, the frame was drastically simplified by using the engine as a load-bearing element. The Yamaha FZ 750 inline-four engine was used as the power unit, with two solid-machined aluminum plates bolted to each side—one for mounting the front swingarm and one for the rear. Due to the engine beeing a stressed member, no connecting frame tubes were needed. The front and rear subframes for the steering head, fuel tank, and monocoque were bolted to these aluminum plates.

Photo provided by Dietmar Edel, Hadamar

In 1988, Bimota presented the fifth and final prototype, whose engine and chassis closely resembled the later production version. This Tesi had no traditional frame but instead featured two 35 mm thick machined aluminum plates, bolted at four points on each side of the Ducati 851 engine. These plates housed the front swingarm, front and rear subframes, front shock mount, and steering mechanism.

In 1989, Bimota entered the fifth Tesi prototype in the Italian Championship race in Misano in the TT Formula 1 class, achieving an impressive second place behind a Honda RC 30. This demonstrated the Tesi’s remarkable potential.

Nearly ten years passed from concept to the production of the Tesi 1D, highlighting the immense effort required for such a small manufacturer. However, perseverance paid off, marking another milestone in motorcycle history.

Bimota continued the hub-center steering concept into the 2000s with the Tesi 3D. The first model resulting from its collaboration with Kawasaki was once again a Tesi. The 2023 Tera represents the latest evolution, transmitting steering movement via brake calipers.

Official press photo provided by bimota.it