Unexpected damages

This BB1 was listed on eBay Kleinanzeigen in Kiel in June 2011 at an attractive price. It had just under 28,400 kilometers on the clock and was from its second owner. The ad mentioned a few issues, but nothing that stopped me from reaching out to André, the seller. He told me that he had been riding the Biposto for seven years and had bought it from the first owner in Hamburg in March 2004. The original owner had purchased it in 2001 from the former importer ZTK in Schneverdingen and registered it on April 19.

André’s descriptions of the bike’s condition were somewhat vague: a cracked turn signal lens, a muffler that needed some work, some paint damage, and a worn-out chain guide. Nothing too serious, so we arranged a viewing at the end of June in Kiel.

End of June, after an appointment in Hamburg, I drove on to the Baltic Sea city. The BB1 was already parked in front of the garage. However, it probably hadn’t always been kept in the garage. Judging by its condition, it had likely spent many nights outdoors by the street over its seven years by the sea. Rust was blooming on the steel parts, such as the rear footrest mounts and the subframe for the cockpit and fairing. The monocoque had plenty of scratches from a tank bag, luggage roll, etc. The overall care left something to be desired, but everything was still within a manageable range. The only major issue was that the chain slider was completely worn through, and the marks on the chain suggested that the swingarm had already been scratched.

During price negotiations, André was accommodating given my to-do list—deal! That weekend, I posted a transport request on the usual online freight platforms. A small transport company from Thalmässing, Bavaria, seemed to have a perfect gap for the job. For an unbelievable €120, they picked up the BB1 in Kiel and delivered it straight to my garage..

This made the BB1 my third Bimota and the first one I would completely disassemble and restore. At the end of September, I started the full teardown, not yet realizing what surprises awaited me – nor how little time I would be able to dedicate to the project in the coming months, which would ultimately stretch out the entire process.

After removing the monocoque, I found more rust on the ignition coil cores, but aside from some scuff marks and 28,000 kilometers’ worth of dirt, everything seemed fine at first.

It wasn’t until mid-February that the BB1 was finally completely disassembled, all parts cleaned, and a clear overview of the necessary work and replacement parts established. The list of required new parts was manageable:

- Chain set

- Chain slider

- Steering head bearings

- Swingarm ball bearings

- Swingarm pivot bearings in the frame

- Oil and oil filter

- Air filter

- Spark plugs, cables, connectors

The 520 chain set is available for €150. A dealer from Bavaria has the original swingarm chain guide in stock – €52 including shipping. The steering head bearing, which confirms my theory of the bike being a street parker in the humid and salty Baltic Sea air, is a standard tapered roller bearing. The ball bearings for the swingarm are also standard. However, the swingarm bearings in the frame are anything but standard. Even after hours of online research, I couldn’t find a suitable replacement part.

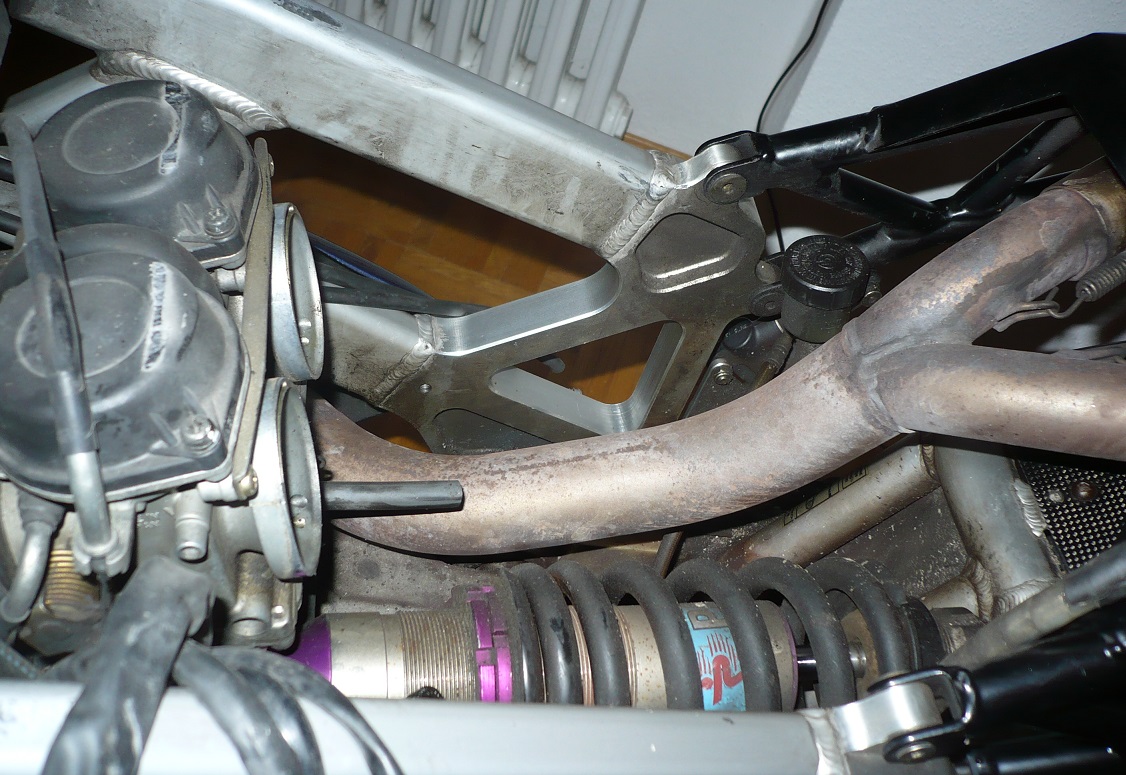

The swingarm mounting in the frame is a real weak point of the BB1. Typically, swingarm axles are firmly bolted into the frame. However, in the Supermono, Bimota used small rubber bushings (silent blocks). Silent blocks are commonly used in shock absorbers or as engine mounts in motorcycle construction to reduce vibration transmission. Their use as swingarm bearings is rather unusual, especially for Bimota, a brand known for ultra-stiff chassis. The silent blocks are a „soft“ component, which contradicts the idea of a rigid swingarm connection at the rear axle. On the other hand, the dimensions of the rubber bushings leave little room for flexibility. With an inner diameter of 14 mm, an inner sleeve of 18 x 2 mm, and an outer sleeve of 25 x 1.5 mm, the vulcanized rubber ring has an outer diameter of 22 mm and an inner diameter of 18 mm – meaning just 4 mm of rubber. That’s not much to dampen vibrations and not much to allow additional movement of the swingarm. Whatever the reasoning behind this design choice, it is clearly under-engineered, and in this BB1, the bushings are completely worn out.

Upon closer inspection, I should have noticed the off-center position of the swingarm axle in the frame during the initial viewing. Given that, I’m quite relieved that the inner sleeve hasn’t completely worn through the outer sleeve and damaged the frame’s mounting point. Fortunately, the issue can be resolved with new silent blocks. However, sourcing suitable replacements is a challenge. The usual Bimota spare parts suppliers don’t stock these bushings, and even silent block manufacturers don’t offer a matching size.

So, a custom-made part based on my drawing, which I send to a few companies after initial phone calls. When they ask about order quantities, I counter with a question about bulk pricing. In the end, I receive two offers. However, only one company from Bavaria is willing to sell just two „rubber-metal high-performance bushings.“ The price: €50 net plus shipping. That’s more than fair for two custom-made parts.

Besides the swingarm mounting, the chain alignment is the second weak point of the BB1. Bimota installed the 650cc BMW engine low and tilted slightly forward to keep the chassis as flat as possible. However, this also places the gearbox output shaft and sprocket just below the swingarm pivot point, requiring the chain to be redirected in the loaded run. As a result, the chain slider on top of the swingarm experiences significant wear. The extreme chain angle becomes even more pronounced if the rear subframe is raised via the adjustable rear shock. When the rider’s weight compresses the rear suspension, the sprocket and swingarm pivot ideally align, reducing the redirection and minimizing friction between the chain and the chain slider. However, since the shock naturally moves while riding, every extension of the suspension alters the geometry and intensifies the chain’s deflection.

Chain tension on the BB1 is a delicate topic. A significant chain slack in an unloaded state is a structural necessity, not a sign of poor maintenance. This also explains why Bimota installed a roller screwed onto the frame in the slack strand to prevent the sagging chain from rubbing against the fuel tank. On my BB1, an additional chain tensioner was even retrofitted.

Over time, the chain gradually wears into the chain slider, which becomes clearly visible on the chain itself. Once the chain slider is worn through, the chain starts eating into the swingarm – unfortunately, this had already happened in my case, and it’s not an isolated issue. A larger sprocket and lowering the rear subframe via the shock absorber can help alleviate or at least improve the situation.

By March, all spare parts have arrived, and reassembly begins step by step. It isn’t until May that all new bearings are installed and the engine, frame, swingarm, and shock are mounted, but it takes until autumn—when the days become colder, shorter, and wetter—before I find more time for the BB1.

Before further assembly, all steel components, such as the rear subframe, passenger footrest brackets, mounting brackets for the exhaust cans, the auxiliary frame for the cockpit and fairing, and the battery box, are sent for sandblasting and powder coating.

Apart from that, only the somewhat worn monocoque needs a new paint job. My „paint shop“ not only takes care of repainting the monocoque but also offers a solution for the silver „Bimota“ and „Supermono“ decals. They have the lettering recreated authentically by a sign painter.

With the restoration, the BB1 Biposto is once again in a condition worth preserving. Considering that only 148 units were built, this makes absolute sense, and I know this won’t be my last restoration.